“It didn’t take much for Chuck to decide that someone was a worthy enough inspiration for a song. Was it justified? Probably not, but it was a way for Chuck to vent.”

DEATH

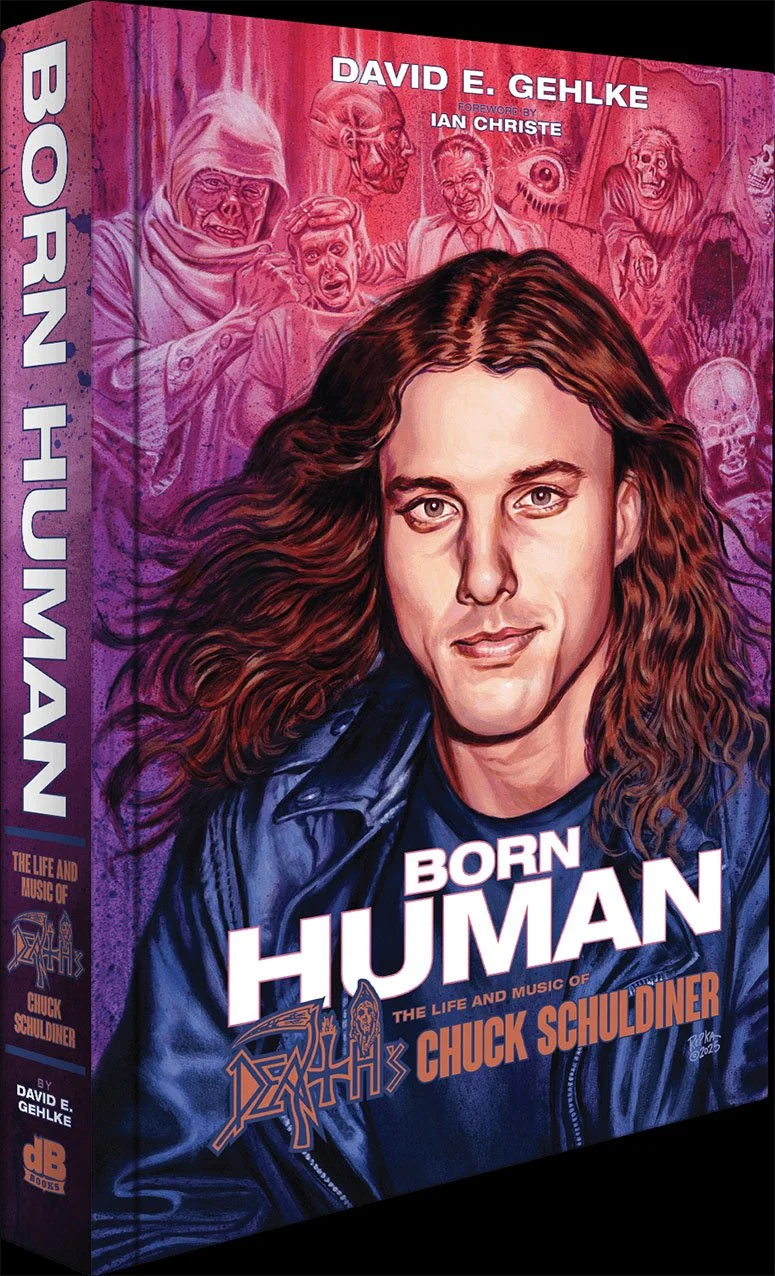

EXCERPT FROM THE NEW BOOK

BORN HUMAN: THE LIFE AND MUSIC OF

DEATH’S CHUCK SCHULDINER

———————————————————

This interview excerpt is part of a larger chapter included in the new book Born Human: The Life and Music of Death’s Chuck Schuldiner (available from Cult Never Dies main store HERE)

Drifting from the Living: Scream Bloody Gore

Combat Records hadn’t heard much from Chuck and Chris Reifert after being notified that Death was going to track Scream Bloody Gore at American Recording Studios in Orlando. Typically, a young band would be assigned a producer and studio by its record company, but this was Death—the new Combat signee that only publicist Don Kaye and a few mid-level employees believed would succeed. The fact that Chuck and Reifert could select the studio showed a surprising lack of care and oversight from Combat. No one at the label had ever heard of American Recording Studios, nor had Chuck and Reifert before they found it in the phone book.

Realizing it was a gigantic red flag for a young death metal band to record at an unknown studio, Combat called Chuck and Reifert for an update. After a mere two days, the sessions had already gone sideways. The staff at American Recording had no idea how to capture the band’s sound no matter how much gesticulating Chuck did about extreme metal. When Chuck and Reifert mentioned other bands as reference points, their pleas fell on bewildered ears. The initial mixes of just Reifert’s drums and a single guitar track were amateurish and nearly below demo-level quality. Alas, Chuck and Reifert had no choice but to admit that they regretted choosing American Recording. (“We felt like we knew what we were doing even though we didn’t,” laughs Reifert.) After one listen, Combat agreed. The label then decided to scrap the sessions and send Death back to California to record with producer Randy Burns in November 1986.

(Cuts from the initial Scream Bloody Gore sessions have since emerged on the 2016 reissue of the album. There is no argument with Chuck, Reifert and Combat regarding the abysmal nature of its production.)

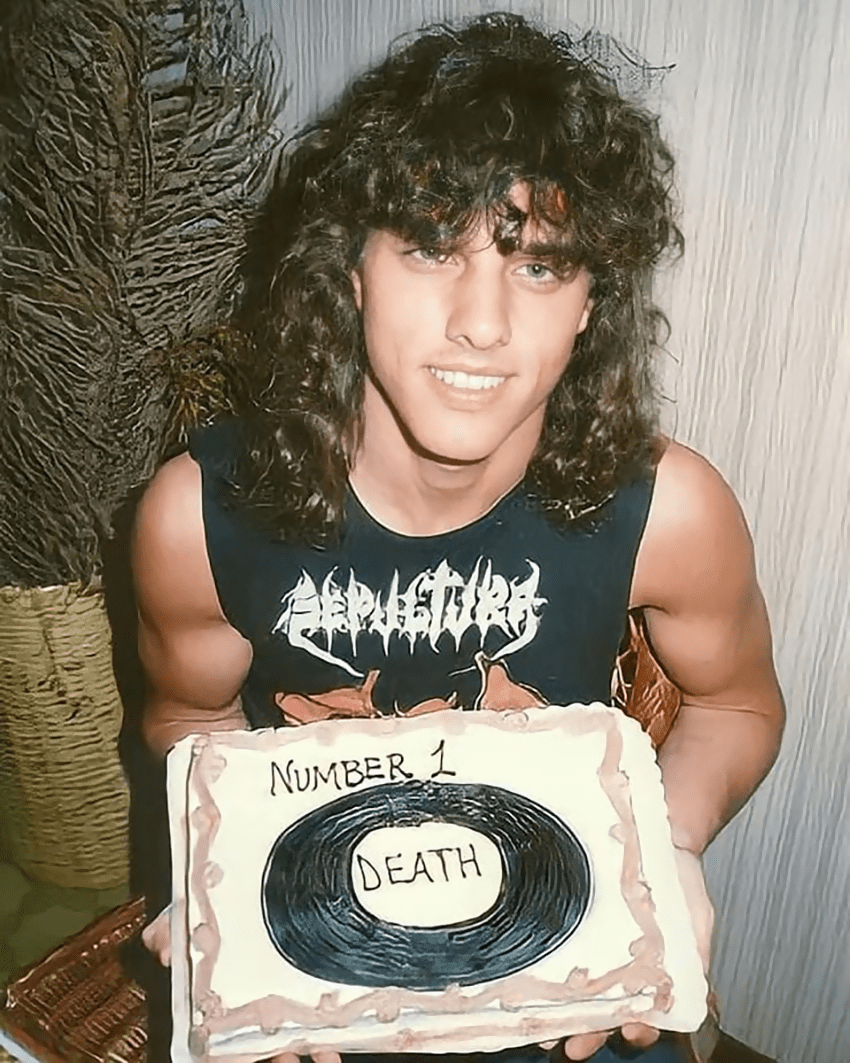

Chuck had every intention of returning to the Bay Area that fall anyway, even if it meant continuing to crash on Reifert’s bedroom floor and having to rely on whatever money his parents, Mal and Jane, could send via the mail. At 19, Chuck was delaying the realities and responsibilities of adulthood for as long as possible. He did not have gainful employment, but he had Reifert, who was still in high school and had since moved with his family to Antioch, three blocks away from Steve Di Giorgio. After spending a few weeks at his childhood home in Altamonte Springs, post-American Recording session, Chuck was back at the Reiferts.

Here, Chuck had plenty of time to reflect on what he had missed (an education) and what he had not done (getting up early in the morning, going to class, doing homework). During this period, Chuck spent most of his daylight hours practicing the guitar by himself or watching TV, then he would get picked up by Di Giorgio for trips to the 7/11 convenience store for Big Gulps and jalapeño Fritos, before settling in for some gore movies. After all of that, it was off to the shared Death/Sadus practice pad.

Speaking of Di Giorgio, he was now very much a part of Death’s day-to-day activities without being an actual member. Chuck and Reifert asked the bassist to learn every song on Scream Bloody Gore with the goal of future Death/Sadus live appearances—a double bill that Di Giorgio had first suggested. In fact, both bands were so sure of joint shows that they went ahead and created mock flyers featuring both of their logos. A real Death/Sadus gig would have to wait—as would Di Giorgio playing on a Death studio album. Surprisingly, Chuck and Reifert never asked Di Giorgio to play on the upcoming recording sessions with Randy Burns, an opportunity that would have likely significantly enhanced the album’s low end. “We were just young and stupid,” says the bassist. “One day, I picked Chuck and Chris up in my Chevy. They told me, ‘We’re going to be gone for a week.’ I thought, ‘Okay, cool. Whatever.’ I didn’t think anything of it, but when you’re 17 or 18 years old like we were, you don’t know how to communicate. That’s how you learn your lessons.”

Unbeknownst to Di Giorgio, Chuck and Reifert were headed to Los Angeles to record Scream Bloody Gore a second time. For as bad as the initial version of Scream Bloody Gore sounded, Chuck, Reifert and Combat all cast their worries aside, knowing that Randy Burns was there this time to helm the sessions. After all, he was fresh off the recording of Dark Angel’s classic sophomore studio album, Darkness Descends. A few months before that, he had produced Megadeth’s classic second album, Peace Sells…But Who’s Buying? And a few months before that, he was at the controls for Possessed’s classic debut studio album, Seven Churches. The commonality between all three (other than being undisputed classics that Burns recorded) was the Combat name affixed to them.

In 1980, Burns assembled a small eight-track studio called Orange County Recorders. His work caught the attention of future Combat label boss Steve Sinclair, who then tapped him to produce the 1981 Hell Comes to Your House punk compilation released on the Bemis Brain Records label, which he co-owned. That work led Burns to engineer Suicidal Tendencies’s 1983 self-titled debut. When Sinclair needed a studio recording done quickly at an affordable price, Burns was his guy.

“Without Steve Sinclair, I don’t know whether I would have had a career or not,” he says. “I was good at delivering stuff on a budget, but I was very obsessive about making records. I didn’t really think about money or trying to become famous. Basically, I’d go from record to record, and after finishing one, I’d start another. That’s all I did. I didn’t get out there and think about, ‘Well, how do I get more money, and how do I get bigger budgets?’ I just didn’t think about that stuff.”

Instead, Burns had to consider how to produce high-quality metal records at a fraction of the cost of other albums. (Peace Sells…But Who’s Buying? can be seen as an exception due to the financial backing of Capital Records, which acquired Megadeth’s rights from Combat.) He faced some growing pains along the way, where he was “making it up” while trying to navigate the speed and intensity of extreme metal. Burns met various studio owners and fellow engineers who believed extreme metal was a lost cause, but he wasn’t discouraged. By the time Chuck and Reifert came to him to re-track Scream Bloody Gore, Burns felt more assured as a producer.

Part of this was attributed to his preferred place of recording in Los Angeles, the Music Grinder. The Music Grinder was a spacious, modern facility with a Neve console, which was state-of-the-art for the mid-1980s. Here, Burns and his assistant engineer, Casey McMackin, helped Megadeth make a massive leap in production quality with Peace Sells from their tinny and thin-sounding Killing Is My Business…And Business is Good debut. When they set foot in the studio, the difference for Death was also immediate , and they marveled at the studio’s size and amenities as compared to the sterile American Recording in Orlando. Chuck and Reifert’s feelings may have been mildly enhanced by the fact that they were high and had a healthy reserve of weed stuffed deep in their pockets.

“I was stoned and thought, ‘Oh, my God. Do we get to record here? Holy smokes!’” says Reifert. “It felt like a fucking airline hangar. I don’t know what it would look like now if I went back, but the Music Grinder felt enormous at the time. That was the first big studio we had been to. We were both like, ‘Oh, fuck. This is so cool.’ We were so excited to be there.”

Burns spotted Chuck and Reifert’s not-so-covert exchanges of cannabis. The producer was forced to play bad cop and gently told the giggling duo that their smoking made him feel uncomfortable, and that they were there to work. Luckily for Burns, Chuck and Reifert came prepared and opted to get “baked out of their minds” after they had finished recording for the day at the hotel, where Reifert took it upon himself to eat so many snacks that he vomited. Chuck did not match his drummer in the munchies-to-vomiting department—he had the rest of the album to track.

Nevertheless, all 12 proposed Scream Bloody Gore cuts had been rehearsed over and over. Chuck and Reifert knew the songs inside and out and had nearly every element of the album agreed upon by the time they arrived at the Music Grinder. With Combat now applying some pressure to get a worthy finished, the Death duo got down to business.

“I was very impressed with their work ethic and how together they were,” says Burns. “They knew exactly what they wanted to do. They could play the songs backward and forwards. Chuck was just spot-on with the guitars. He really nailed the stuff. I was impressed with the fact that they were so organized and on top of the material, were really hard workers and focused in the studio. It’s a hard job making these records.”

The Scream Bloody Gore sessions were long—Chuck, Reifert, Burns and McMackin usually started around 10 in the morning and wrapped at eight at night. Thanks to his rigid practice schedule with Chuck, Reifert needed only a few days to cut his drums. The Music Grinder featured a 25-foot ceiling made of wood, contributing mightily to Reifert’s thunderous drums. Burns put Reifert’s kit in the corner of the room and let its natural sound take over. “There’s no reverb on his drums,” says the producer. “The drums have this natural darkness to them from the big room.”

Chuck tracked all rhythm guitars, lead guitars, bass and vocals. He took his parts very seriously and was not one to waste time—he quickly moved on to double-tracking his guitars after the first layer was complete, then moved on to leads. It’s safe to assume that Chuck circa Scream Bloody Gore was a far better rhythm player than lead. He never learned music theory and was unable to articulate scales and modes; thus, his solos occasionally displayed a disharmonic flair on the album. The lead guitar style that would soon come to define the Death sound was already there: Chuck’s patented bursts of tremolo-picked notes were always well-constructed and even trended in the melodic direction on “Evil Dead.”

Scream Bloody Gore is easily Death’s most primal studio album. Chuck’s riff repertoire at the time was either manic tremolo picking or meaty power chords, with the appropriate phalanx of evil guitar harmonies, particularly on the album’s most popular number, “Zombie Ritual.” The onus on speed is a snapshot into how much Chuck was listening to Slayer at the time, a band whose seamless transitions and avoidance of riff clutter were an apparent influence. His riffs are often decidedly simple (for example, the intro power chords to “Infernal Death,” which also re-appear on the closing title track) yet highly effective and engaging, such as the chunky “Regurgitated Guts” and the variations found on the chorus of “Baptized in Blood.” For as embedded in the firmament as Scream Bloody Gore has become, its enduring quality is a result of just how catchy and memorable the songs are.

The three-song Mutilation demo showcased Chuck’s capabilities behind the microphone as unforgivingly brutal, yet still decipherable. The same holds true for Scream Bloody Gore, a performance that future death metal growlers have routinely cited as having a profound influence. Chuck’s patterns and cadences were simplistic, and he understood the true value of a memorable passage and chorus. Instead of the rapid-fire, word-salad delivery that most thrash bands (and Possessed) employed, Chuck’s vocal patterns were deliberate, even patient, as he was prone to letting his lines breathe.

The album does not lack satisfying moments in the vocal department, though. It starts with his first words on “Infernal Death:” simply, bluntly, “Die!” From there, the savage couplings found in the chorus of “Zombie Ritual” or his acidic mutations in the chorus of “Denial of Life” rank among some of the most memorable vocal lines in death metal history as do his lines in the pre-chorus of “Baptized in Blood” where Reifert picks up the pace, or his over-zealous one-liner in “Torn to Pieces” of “man eating man!”

The disparity between Chuck’s regular speaking voice and death metal vocals initially threw Randy Burns off guard. He wasn’t the only one. Chuck’s pseudo-California-surfer speaking voice had long drawn comparisons to Jeff Spicoli, the lovable high school stoner played by Sean Penn in the 1982 movie Fast Times at Ridgemont High. Chuck’s propensity to casually insert “like,” “you know,” “whatever” and “dude” into his vernacular was often a source of amusement and puzzlement for his bandmates and friends. Chuck was born in Long Island, NY. He lived in Altamonte Springs, FL, thousands of miles from the California beaches. No one can quite pinpoint why Chuck sounded like a surfer—not even his family, none of whom sound like him. Chuck’s speaking voice was ultimately his and his alone, which made his ability to quickly reel off some of the most brutal vocals known to man circa 1986 all the more fascinating. (For the curious, nearly all interviewees for this book, unprompted, said that Chuck sounded like a surfer.)

Several of the songs’ lyrics had undergone mild revisions from the Kam Lee era, starting with the removal of satanic references. Throughout his career, Chuck was never willing to cross this line, despite never fully establishing his religious stance. Possessed, Slayer and Venom had already staked out the territory, and so had another Chuck favorite, Danish traditional metallers Mercyful Fate. At the time, the “t” in Death’s logo remained inverted, perhaps the only signal that Chuck still wasn’t ready to abandon the band’s early anti-religion angle completely.

Half of the album’s lyrics are generated from Chuck’s horror movie collection. “Zombie Ritual” is based upon Zombie 2, “Regurgitated Guts” is from City of the Living Dead, “Torn to Pieces” is drawn from Make Them Die Slowly, “Evil Dead” takes its cues from The Evil Dead, the title track is inspired by Re-Animator and “Beyond the Unholy Grave” is taken from The Beyond. However, in keeping with Chuck’s desire to be the most brutal band in metal, the lyrics on Scream Bloody Gore are primitive—at times even misogynist, particularly “Sacrificial,” which initially went under the title of “Sacrificial Cunt.” The title remained in place until Combat intervened out of fear of being confronted by the Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC), which, at the time, was sending shockwaves through the music industry by targeting bands they deemed vile, sexist, satanic or plain old inappropriate. As it was soon to become known, “Sacrificial” is about Possessed fan club manager and one-time Chuck friend Krystal Mahoney, whom he started to disparage with similar, unfortunate language after their relationship broke down.

“It didn’t take much for Chuck to decide that someone was a worthy enough inspiration for a song,” says writer Borivoj Krgin. “I think it was just something that he was feeling angry about at the time and wanted to express it in a song. Was it justified? Probably not, but it was a way for Chuck to vent.”

“I like the fact that Chuck really understood the thing about being offensive as being something that you want to do,” adds Burns. “I remember I was in the studio with one band around this time, maybe a few years earlier. They had a song, and it said, ‘Fuck’ in the lyrics. The guys were like, ‘Randy, what do we do? Do we leave this in here, or do we take it out?’ It’s like, ‘You’re not going to be on the radio. Let me ask you this: Would your mom be offended if you left it in?’ They said, ‘Yes, probably.’ I said, ‘There’s your answer. You want to leave it in.’ Chuck didn’t need any help with that. He knew exactly what he wanted to do.”

Chuck experienced very few issues when cutting vocals for the 12 songs on Scream Bloody Gore, although Burns recalls a few moments where he needed to take a breather. Death hadn’t played a live show in nearly a year, and Chuck’s stamina was not quite where he wanted it to be. Chuck had proper vocal technique (he rarely lost his voice), but the intensity of the Scream Bloody Gore sessions was taxing. “He did these blood-curdling screams—they were incredible,” says Burns. “A couple of times, he would do those, and he’d have to go and grab something and sit down because he would be a little dizzy. I was really impressed at just how intense he was. He put everything into it.”

Chuck and Reifert emerged largely satisfied with the Scream Bloody Gore sessions. The only downer was that Chuck was not around when Burns mixed the album and soon had complaints that his guitars could have been “louder.” Beyond that, Chuck and Reifert made good on Combat’s gamble by recording the album a second time. The label and others close to Chuck then started to ask how—and when—he was going to complete Death’s lineup. Again, logic would assume that they would have asked Sadus bassist Steve Di Giorgio, who didn’t find out the pair recorded Scream Bloody Gore until it was too late.

“We were in my truck smoking a doobie and hanging out,” he says. “Finally, I asked, ‘So, where did you go?’ Chuck and Chris paused and said, ‘Oh, we recorded the album.’ I was like, ‘You recorded the album? What do you mean? Did you record the album? Like all the songs we were jamming?’ Chuck goes, ‘Yeah, dude. It sucked! I had to do all the rhythm guitars, my leads, the bass and vocals. It was too much.’ I was like, ‘I’ve been here the whole time jamming with you guys! You could have asked me!’ Reifert hit Chuck in the arm and was like, ‘See! I knew we should have asked him.’ But I don’t think Chuck and Reifert wanted to impose. We were best friend bands. I don’t think Chuck wanted my Sadus guys to feel like they were stealing me. Maybe it’s for the better.”

With Scream Bloody Gore complete and handed over to Combat, Chuck returned to Altamonte Springs for the holidays. It was still up in the air whether Chuck would actually return to the Bay Area—he did not give Reifert or Di Giorgio a firm commitment either way. Death, though, was still a “band” and making inroads toward adding new members, which is where the legend of John Hand begins and quickly ends.

This interview excerpt is part of a larger chapter included in the new book Born Human: The Life and Music of Death’s Chuck Schuldiner (available from Cult Never Dies main store HERE)